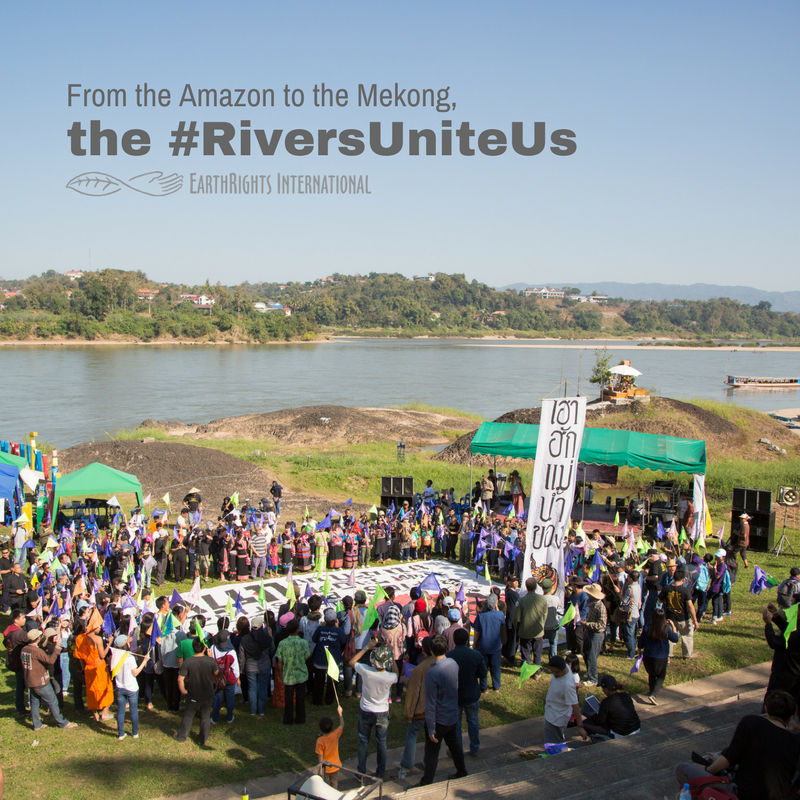

International Day of Action for Rivers Reminds Us All To Protect Our Rivers.

Rivers are critical shared resources that belong not to one nation, but to all who are dependent on them. Our work often revolves around rivers and the people who rely on them for food, water, and transportation. From fighting Occidental Petroleum’s oil contamination in the Corrientes River basin in the Amazon since 2007, to standing by indigenous communities in Peru who still face major oil spills today, to challenging mega dams on the Mekong river and its tributaries in Southeast Asia — we know the importance of free flowing and clean waters to indigenous communities and fishing communities around the world.

Earth rights defenders, and specifically river defenders, are under threat in many places. We all remember Berta Cáceres, a Lenca woman who successfully fought off the Agua Zarco dam in Honduras, who was killed in her home just over a year ago. Other defenders, including those fighting the Chadin II dam connected to the Conga mining project in Peru, are also under threat.

We stand together with communities protecting their water and rivers today and every day.

A free-flowing river

The construction of mega dams is a major way in which the flow of a river and the life in and around it are affected, and consequently one of the ways in which governments violate fundamental rights of the people who depend on rivers. Therefore, on March 14, 1997, in Curitiba, Brazil, the International Day of Action for Rivers was adopted in commemoration of the struggle against the construction of dams and the defense of rivers.

Originating on the Tibetan plateau and meandering through China, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia to the Vietnam Delta, the Mekong River feeds and sustains millions of people. In Thai and Lao languages, the word ‘Mekong’ connotes ‘mother.’ Together with its tributaries, the Mekong generates and supports some of the richest and most diverse ecosystems in the world. It is also home to over one thousand species and is second only to the Amazon River in terms of biodiversity.

Since 2006, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand have granted approval to start planning 11 mainstream hydropower dams despite widespread protests from downstream countries where the lives and livelihoods of millions are in jeopardy.

The Don Sahong Dam in southern Laos is under development less than two kilometers from the Cambodian border. If built, this dam will block a major passage for the many species of fish migrating up and downstream to feed and to spawn, which provide an essential food and protein source for Cambodian people across the border.

Cambodian communities rely heavily on fish from the Mekong and its tributaries as an essential source of food and livelihoods, with fish forming up to 80 percent of the protein in Cambodian diets. Many villages are situated along rivers, where the use of the water and its resources are a way of life. Healthy rivers support access to clean water, food, livelihoods and indigenous traditions and cultures.

Any visitor to Cambodia will notice that the country is undergoing rapid change through massive influxes of investment and development over the past decade. Increasingly, hydropower dams form part of this change. The Lower Sesan 2 (LS2) dam is under construction on the Sesan River, a major tributary of the Mekong. Although a tributary, the Sesan River is an important migration route and breeding ground for fish species from the Mekong River.

River defenders under threat

The construction of dams in Chile, Paraguay, Colombia, Brazil, Honduras, Mexico and Peru have had dire consequences for communities and the environment. These mega projects are often carried out without community approval and without rigorous and serious technical analysis, such as an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA. Analysis like this can warn about the negative effects that these projects may have, especially when they are done with the appropriate participation and consultation of the communities.

Peru is second only to Brazil in Latin America, with the largest number of hydroelectric plants in operation, under construction or planned, and the Peruvian Amazon is one of the places most affected. The Rio Marañón is one of the most important water sources in Peru and a main tributary of the Amazon River, and there are plans to build more than 20 dams, including the Chadín hydroelectric dam.

On the banks of the Marañon River, indigenous communities are worried that the Chadín II dam will flood their villages and leave them without a way to support themselves. (Learn more about it from our Spanish report Energía, Bosques y Pueblos en el Marañón). There are additional concerns that the dam is being pushed forward not because of the energy demands of Peruvian citizens, but because of the nearby Conga Mine—itself the subject of community protests and subsequent violent crackdowns by police. The belief is that the mine will not remain economically viable without the local source of cheap energy that the dam can provide.

Those who oppose the Chadin II dam project and the Conga mine are under threat and have been physically attacked by the police (in 2011 and 2013, for example).

Another well-known example is that of Berta Cáceres who organized the Lenca people of Honduras and successfully pressured the world’s largest dam builder to pull out of the Agua Zarca Dam. Since the 2009 coup, Honduras has experienced an explosive growth in destructive megaprojects that will displace indigenous communities. Almost one third of the country’s land is set aside for mining concessions, creating a demand for cheap energy to power future mining operations. Like the Chadín II dam and the Conga mine in Peru, the Honduran government approved hundreds dam projects around the country.

Berta Cáceres was killed in her home just over a year ago. Various arrests have been made in connection with the murder, including U.S. trained military personnel, a Honduran special forces sniper, and a manager for the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam which Berta Cáceres had opposed.

Keep the rivers clean!

In 2016, the Chiriaco River in the Peruvian Amazon was painted black with more than 2,000 barrels of crude oil. The spill has severely impacted the river, and the lives in and around the river, including the eight indigenous communities with about 5,000 people who depend on the river for their survival.

The North Peruvian Oil duct II, operated by PetroPeru, ruptured, releasing the oil into one of the tributaries of Marañon River, which in turn flows into the Amazon River toward Brazil. Later that year, there was another spill in the Morona river basin in Mayuriaga, that also flows to the Marañon. This spill affects 10 more indigenous communities and around 3,500 people.

These spills are not without precedent.

In July 2014, more than 2,600 barrels of spilled oil-impacted communities in Cuninico and 7,500 barrels in San Francisco near the Pacaya Samiria National Park. The spills are causing great damage to the wellbeing of the indigenous people, whose health and livelihoods are affected. We are supporting the communities in their legal proceedings with local judges. In an unprecedented ruling in February 2017, a judge in Nauta, Peru ordered to assist indigenous victims of oil spills in Peru.

Rivers, also known as Mayu, Parana, Jawira, and Rio in Quechua, Kukama, Aymara, and Spanish, urgently require a commitment governments to adopt actions for their defense and protection. To speak of river protection is to speak of respect and protection of human rights, including the right to a dignified life, the right of indigenous communities to develop and have their own traditional forms of life, and the right to the environment.

That is why, on this day, we are calling for the respect and care of rivers, and demanding that governments comply with their international obligations to respect and ensure the right to the environment, health, water, and life. We will continue to join efforts of the communities we work with, denounce perpetrators where we see them and work to prevent these projects and their interests, whether public or private, from destroying ecosystems, communities, and sacred sites. Defenders can not continue to be silenced in the name of these projects.

There are many battles to fight, and many rivers that are at stake. We have to remember, that from the Amazon to the Mekong, rivers unite us and we must fight to protect them.

Join the conversation and share this with your networks: