At EarthRights International, we train defenders and build networks to lead movements for lasting change. Our transformative education and training programs sow the seeds of hope that blossom into collective action against injustice.

We first launched our education and training initiatives in 1999, with the EarthRights School. Since then, our training programs have grown significantly in scope and impact. In 2025, we completed over 20 training and knowledge-sharing events and engaged with over 450 defenders, advocates, and community leaders.

We work to strengthen the knowledge and skills of the next generation of environmental defenders by providing them with learning sessions on topics such as legal rights, community-led resistance, evidence gathering for documenting abuses, and negotiating with complex stakeholders. These initiatives reach participants from all corners of the globe, from the cloud forests of the Mekong to the wetlands of the Amazon.

Through this work, we empower defenders to protect themselves and their communities from threats posed by governments and corporations. We also strengthen skills and capacity to facilitate long-term, structural transformation.

This work has become the cornerstone of our strategy to achieve a fairer world in which Indigenous communities and the lands that they fiercely defend are protected for generations to come.

Learn more about our innovative education initiatives and hear from participants around the world today.

The Indigenous Legal Defense Program, Latin America:

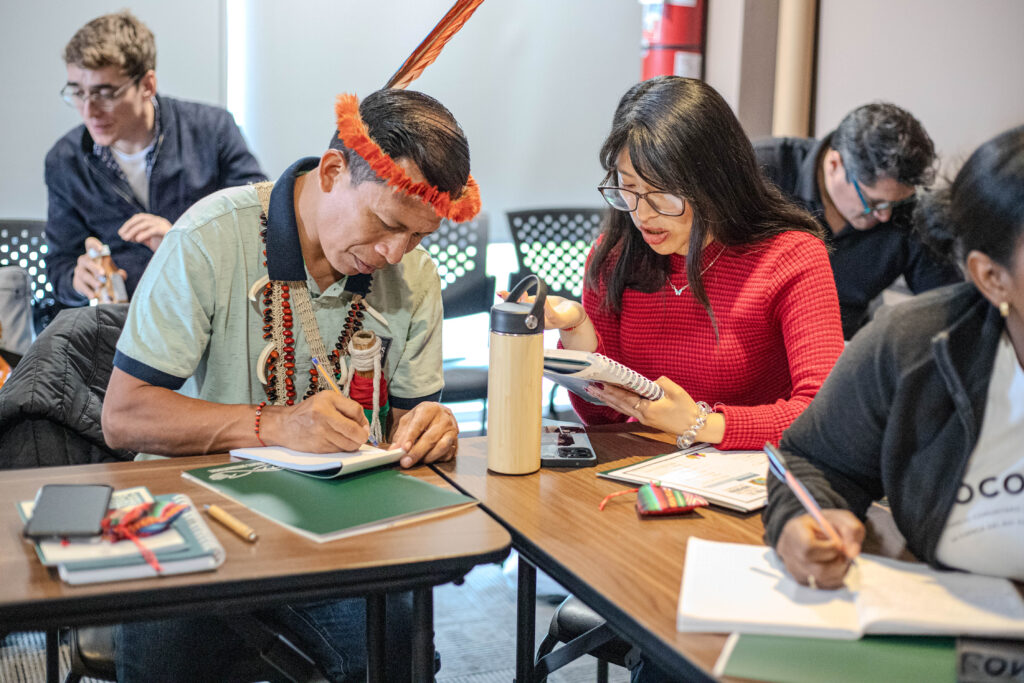

The Indigenous Legal Defense Program engages with environmental defenders from across Latin America to provide them with an opportunity to learn new skills and create networks for the sustained defense of ecosystems and communities in the region. The majority of program participants are from Indigenous and Afrodescendant communities.

Participants learn about how to conduct effective campaigns, use legal mechanisms to defend the rights of their communities, and incorporate communications strategies into their advocacy work. Participants are lawyers, advocates, and community leaders from diverse backgrounds, education levels, and perspectives.

“Our training program is designed to provide technical and strategic knowledge, skills, confidence, and especially to allow participants to exchange experiences, learn from each other, and create networks to continue their struggle for justice and rights,” said Juliana Bravo Valencia, Latin America Regional Director of EarthRights.

Opi Nenquimo

Opi Nenquimo was born and raised in this territory. As the president of the Waorani Organization of Pastaza, he is a forest guardian and a defender of the Indigenous Waorani people. His story is also the story of a millennia-old nation that, in the face of expanding extractive projects across the region, has had to reinvent its forms of resistance to survive.

Nenquimo took part in EarthRights’ Indigenous Legal Defense Program this year. His participation marked a turning point in his approach to leadership. “This is a tool we will use in our territories and share with our youth. We will share this legal and human rights knowledge to strengthen our community capacity,” he said.

Surrounded by defenders from across the region, Nenquimo recognized that the challenges facing Waorani communities in Ecuador mirror those experienced by his peers from Chile to Mexico. “Here, in the program, we are among people from different parts of the world… That living struggle nourishes us and strengthens us,” he said.

For Nenquimo, completing this training represents a commitment to his community. The legal tools and communications strategies he learned during the program are resources he plans to bring home to help develop collective defense strategies with other members of his community.

The EarthRights School, Mekong Region:

The EarthRights School offers a unique blend of education in human rights, environmental law, and community advocacy, as part of a seven-month residential program in the Mitharsuu Center, Chiang Mai, Thailand. The program combines interactive classroom learning with field research to ensure that students put the tools they are learning immediately into practice.

Participants are from Indigenous and rural communities across the Mekong region and many have experienced environmental and human rights abuses firsthand. The program is designed to prepare young leaders from diverse backgrounds to return to their communities armed with tools for change.

“The content and learning methods are adapted to the needs of our participants each year, according to the principles of inclusive, non-formal, adult learning. The language of instruction is English, however, we provide language learning support, and resources in the national and local languages of the participants,” said Krisztina Gyory, Senior Training Manager for EarthRights.

The Alumni Network, Mekong Region:

After participating in EarthRights training programs, alumni from Mekong countries go back to their communities, where they continue their advocacy in defense of the environment and human rights. However, many continue to face risks and obstacles, such as criminalization and security threats.

In response, EarthRights created the renewed Alumni Network in 2021 to connect program graduates through a platform for continued learning. The Alumni Network encourages in-country and regional collaboration from graduates from Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos, across a wide range of different ethnic communities and advocacy areas.

Network members receive up-to-date skills training, toolkits, and resources to address challenges they continue to face. Additionally, the network provides practical tools to alumni to navigate the risks they face in their advocacy, including security guidance and mental health support.

Suwannee

Suwannee’s goal is to restore that respectful relationship. It was this objective that led her to apply to the EarthRights School program in 2021. As a student at the EarthRights School, Suwannee improved her advocacy skills and created lasting networks with other environmental defenders from across the Mekong region. She gained knowledge about how to examine complex power structures, how economic pressures affect Indigenous communities, and how to create collaborative advocacy plans that can bring about lasting change.

After graduating, Suwannee returned to her community with a renewed sense of purpose. She now works with the Mekong Akha Network for Peace and Sustainability, protecting Indigenous rights and connecting local women and youth groups to strengthen their networks.

In 2024, Suwannee joined the EarthRights School Alumni Network. She also became a member of the Thai alumni core team in the same year, fostering collaboration and reconnecting alumni through meetings and events. Through her work, Suwanee continues to prove that reconnecting with nature is not only an act of preservation but the path toward a more just and sustainable future.

The Congo River School, Democratic Republic of the Congo:

EarthRights launched the Congo River School in partnership with African Resources Watch (AfreWatch) in 2023 to train leaders and activists impacted by damaging mining and development projects across the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A first training program was held the same year, in which 24 participants learned about legal and advocacy mechanisms they could use to protect their communities from harm. In 2024, EarthRights organized the second installment of the Congo River School to build on the knowledge gained in the first training. The Congo River School will hold a third and final training program in 2026.

The curriculum provides participants with practical tools and skills to advocate for their rights and identify community goals and needs. Participants have already presented 12 action plans that established a foundation for continued advocacy, education, and accountability efforts within affected communities to ensure sustained positive outcomes.

The Mekong Legal Advocacy Institute (MLAI), Mekong Region:

EarthRights established the MLAI in 2009 to provide a forum for young lawyers and legal advocates from the Mekong region to share experiences, learn and develop new legal and advocacy strategies, and take effective coordinated action on environmental and social issues.

Our annual MLAI workshop is a three-week, in-person, intensive training program which takes place at the Mitharsuu Center in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Participants learn about legal tools, mechanisms, and strategies to strengthen recognition of human and environmental rights in the Mekong region.

The training focuses on legal advocacy within communities, including campaigning, challenges in legal cases, Indigenous rights, environmental impact assessments (EIA), and procedural rights of communities and environmental defenders. Graduates of the MLAI continue to stay engaged through the Mekong Legal Network (MLN). The MLN is an independent group of legal professionals and civil society leaders that meet twice a year to strategize about the use of legal tools for the defense of human rights and the environment.

Dear

As a young Tai Lue Indigenous woman and law graduate of Chiang Mai University, Dear always understood that the law on paper and in practice can be worlds apart. Thailand’s 2014 coup, she says, played a defining role in that realization.

In 2024, Dear joined the Mekong Legal Advocacy Institute (MLAI) program, an experience that she describes as transformative. Through the intensive, two-week-long program, participants gather at the Mitharsuu Center in Chiang Mai to learn about international, regional, and national legal frameworks for the protection of environmental and human rights. They also learn about corporate accountability, preparation of lawsuits, and the protection of defenders across the Mekong region.

“When I joined the MLAI training program, this opened up an opportunity to learn about environmental law, legal pathways, and how to submit a lawsuit,” she says. Through the program, she learned about different legal cases, allowing her to compare strategies and examine how political systems shape legal outcomes. “I learned about cases from many different countries. I made comparisons, analysed the advantages of cases, and worked on policy issues.”

Dear wasn’t just learning at MLAI – she was also contributing. Her extensive experience working with communities in Thailand allowed her to participate proactively in discussions on using the law to protect communities at risk of harm. “During the MLAI, I shared my experiences on how to work with the Administrative Court in Thailand, how to work with communities, and how to empower communities in the Thai political context,” she says.

Her participation in MLAI helped her to deeply reconnect with the reasons why she began studying law in the first place: her strong belief that Indigenous communities deserve respect, autonomy and the right to chart their own future. “It’s really unfair that they don’t have a space to decide their own destiny, what they want to be, and what is best for them,” she says. “Everyone should have equality in terms of deciding the policies and laws that impact them.”

Global Education Initiatives:

Many environmental defenders across diverse geographies face similar challenges in their work to protect their communities and land from the harms of development and extractivist projects. Our global education team works to develop solutions to these shared problems and threats.

EarthRights launched the Global School in 2022 to help defenders build connections, exchange ideas, and create an international network of climate justice leaders. EarthRights also works to develop additional, specialized training sessions that address issues that impact defenders globally and that require improved cross-border collaboration. These sessions explore topics from the criminalization of defenders to cybersecurity threats.

The team supports defenders globally to participate in discussion forums of strategic importance, where they can raise awareness about local challenges and strengthen their action plans for achieving lasting change. In 2024, EarthRights co-convened a South-South Learning Exchange event in Chile 37 civil society representatives from Africa and Southeast Asia before the Escazú Conference of the Parties (COP). During the workshop, participants learned from defenders from Latin America and representatives of United Nations agencies about the creation of the Escazú Agreement.

At the heart of our education work is a commitment to local-to-global strategies that grow frontline causes into collective action with regional and international reach. Through our global education initiatives, we work at local, regional, and international levels to address issues rooted in community struggle, ensuring that solutions reflect local realities while achieving broader impact.

By grounding our training and education efforts in the lived experiences and leadership of environmental defenders, we ensure that the legal and advocacy tools we develop remain relevant, responsive, and rooted in community priorities. This model allows grassroots knowledge to shape global agendas and ensures that global decisions strengthen, rather than overshadow, the power of local movements.

As we enter our 2025-2029 strategic period, EarthRights renews its promise to accompany defenders with bold, community-centered education initiatives that protect human rights and safeguard the environment. Together with our partners, supporters, and the communities who guide us, we will continue building a world where justice, accountability, and the voices of defenders lead the way forward.

Want to support our global education initiatives? Donate to EarthRights International today, and you could help defenders stand up for their rights and the environment.